The Natural world is one that is neither stable nor permanent, and the built world by contrast is often thought of as its opposite, concrete and stubborn. These two opposing environments have served as the inspiration for the architecture I have studied and as the focal point of my artwork regarding nature and the built environment. However, to say that I am interested in the differences between the natural world and the man-made one would be misleading. Even when compared semantically "natural" and "man-made" are two words that are not necessarily opposed. The opposite of nature is the un-natural, a proverbial can of worms that conjure anything from hideous deformities to uncanny otherness. By contrast, the "man-made" is relatable, dependable even. None the less, it is clear that man-made is not coincident with being opposed to nature.

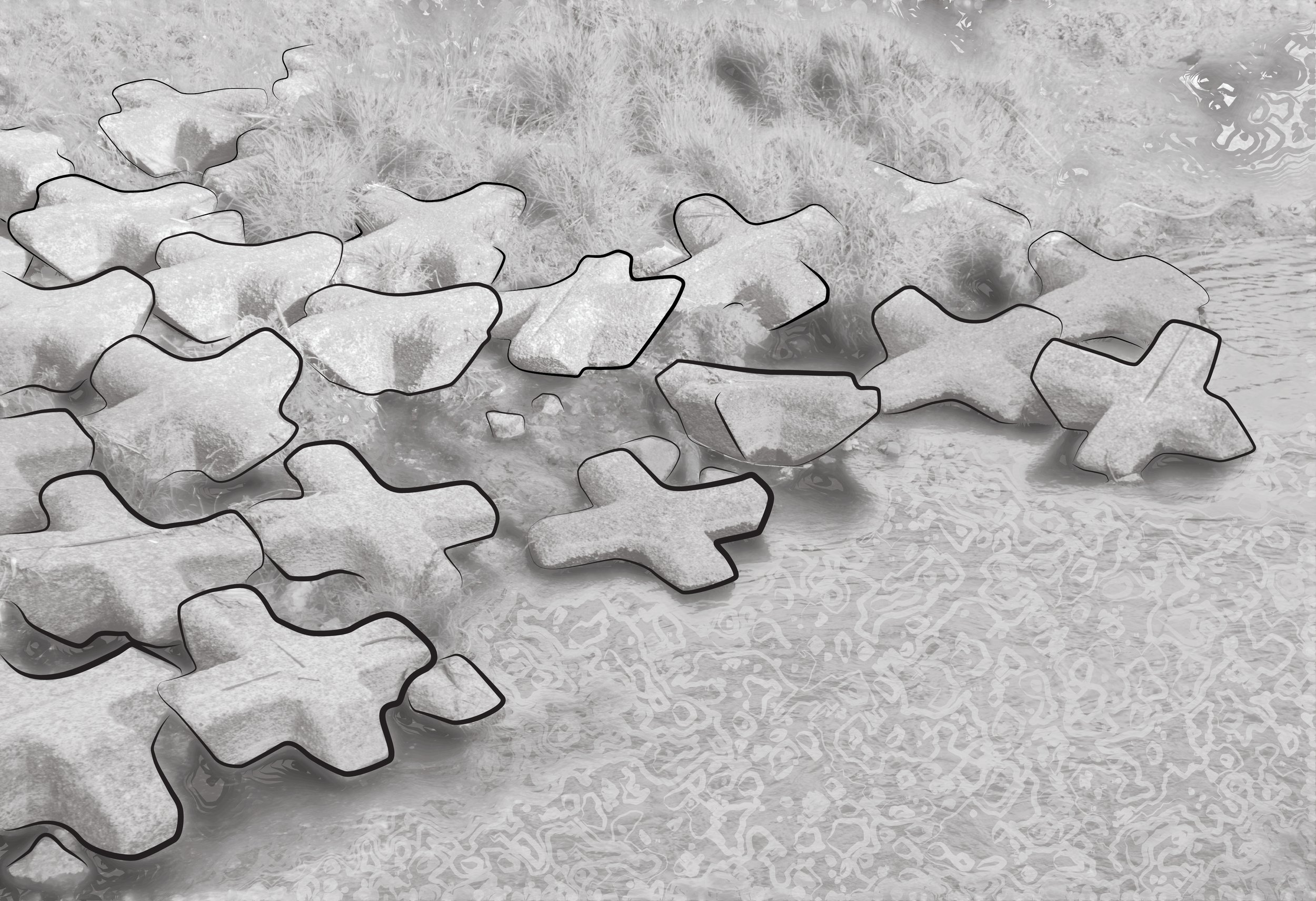

With this being said there are few forces in the world that are so readily at odds with each other. To be made, something must first be built, and to build is to take from the natural world and reallocate to the built world. However, this is not so much a process of destruction and rebirth as it is one of reallocation. The tree does not cease being a tree once it is removed from the ground and rearranged into a house. It has just entered another state of being. This seems like a simple enough concept once explained in this manner, but it has a uniquely eastern sentiment, but one that has proven rather elusive in the west.

The comparison of the west to east is perhaps as incomprehensive as the comparison of the natural environment to the built one, but a different kind of comparison may do the trick. Greco-Roman philosophy and Buddhist philosophy are perhaps as different as any two philosophies could be, this being made clear through the concepts of dualism and monism respectively.

For something to be dualistic, it must possess two parts, often in conflict with one another or representing two very distinct states. This idea is embedded deeply in Europe's history and is most notably realized in the separation of body and mind that is at the core of Greco-Roman sentiment.

I am admittedly less knowledgeable in the practices and beliefs of Buddhism, but I believe that is safe to say that where western philosophy is widely considered to be dualistic, Buddhism is distinctly monistic. Instead of characterizing the world in terms of things that are distinctly different, Buddhism seeks to define everything as part of a greater whole.

This is where my analogy of the tree as building comes back into play. As western thinkers we are not trained to see the world in ambiguous terms, it eludes us through our compulsion to categorize it, and all the while the reality of it all is right there before our eyes. Buildings can be just as temporal as the leaves on the trees, just as those trees can be just as strong and enduring as a stone temple built to stand for centuries.

I hope that my fascination with this wonderful world of the in-between piques your interest, and I invite you to reconsider the way that that you look at your world as well, even if only in some small way.

In this video interview with Harrison Marek and Bijoy Goswami, the two explore the prevailing concepts that drive eastern and western philosophy, through the...